Teachers struggle to reach seemingly unmotivated students. It is true that the degree to which students are “self motivated” is a key factor of student academic success, and it is probably true that we cannot actually motivate students. Teachers too often try low-impact or no-impact motivation strategies thinking they will help. The good news is that there are things that teachers can do to create the conditions for students to be self motivated, and there are at least 6 high-impact strategies for creating the conditions for students to be self motivated.

Teachers struggle to reach seemingly unmotivated students. It is true that the degree to which students are “self motivated” is a key factor of student academic success, and it is probably true that we cannot actually motivate students. This is the old idea that we can lead a horse to water, but we cannot make him drink.

The idea falls flat, however, when it is accompanied with the assumption that there is nothing teachers can do to help students be more self-motivated. This is compounded by the fact that teachers too often try low-impact or no-impact motivation strategies thinking they will help (probably because they are used so often and seem to have legitimacy, even if they don’t work well). These low-impact/no-impact motivators include grades, detentions for not doing homework, bribery rewards, showing enthusiasm, being nice to students, or statements like “you’re going to need this in high school (or college, or work, etc),” or “it’s going to be on the state test.”

The good news is that there are, in fact, at least 6 high-impact strategies for creating the conditions for student to be self motivated. This is the idea that we may not be able to make a horse drink, but we can certainly salt his oats.

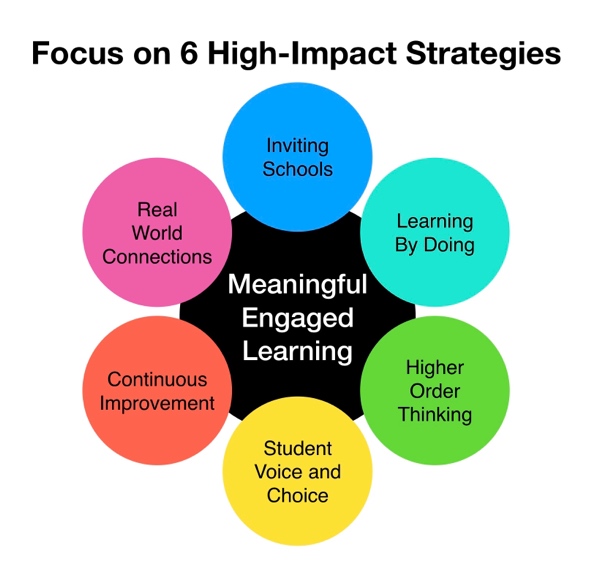

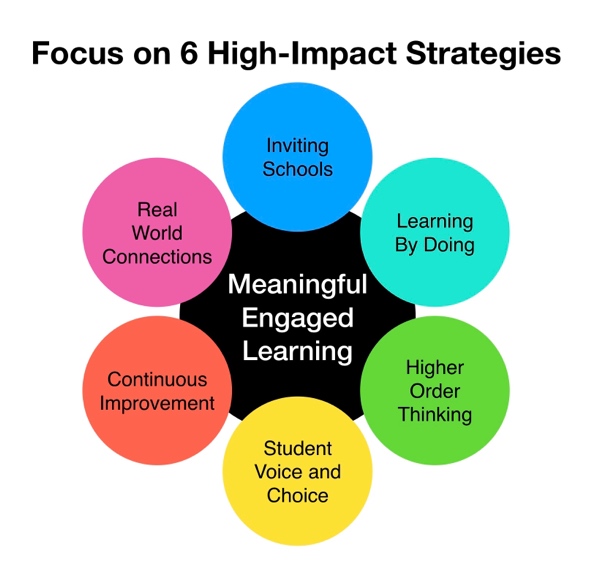

One approach to creating the conditions for student self motivation are the 6 Meaningful Engaged Learning Focus Strategies which grew out of me dissertation so long ago. Schools working to improve student motivation, engagement, and achievement concentrate on balancing six focus areas:

One approach to creating the conditions for student self motivation are the 6 Meaningful Engaged Learning Focus Strategies which grew out of me dissertation so long ago. Schools working to improve student motivation, engagement, and achievement concentrate on balancing six focus areas:

- Inviting Schools

- Learning by Doing

- Higher Order Thinking

- Student Voice & Choice

- Real World Connections

- Continuous Improvement

Here’s a brief overview of each strategy.

Inviting Schools: Sometimes, it may seem like this one has little to do with academics or engaging students in learning, but positive relationships and a warm, inviting school climate are perhaps the single most important element to implement if you are working to reach hard to teach students. I have heard over and over again from the students I have worked with that they won’t learn from a teacher who doesn’t like them (and it doesn’t take much for a student to think the teacher doesn’t like her!). It’s important for everyone in the school to think about how to connect with students and how to create a positive climate and an emotionally and physically safe environment. Adult enthusiasm and humor go a long way, and teachers are well served to remember that one “ah-shucks!” often wipes out a thousand “at-a-boys!”

Learning by Doing: When you realize that people learn naturally from the life they experience every day, it won’t surprise you that the brain is set up to learn better through real experiences, in other words, active, hands-on endeavors. Many students request less bookwork and more hands-on activities. The students I studied were more willing to do bookwork if there was a project or activity as part of the lesson. Building models and displays, field trips and fieldwork, hands-on experiments, and craft activities are all strategies that help students learn.

Higher Order Thinking: It may seem counterintuitive, but focusing on memorizing facts actually makes it hard for students to recall the information later. That’s because the brain isn’t accustomed to learning facts out of context. Higher order thinking (e.g. applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating, within the New Bloom’s Taxonomy) requires that learners make connections between new concepts, skills, and knowledge and previous concepts, skills, and knowledge. These connections are critical for building deep understanding and for facilitating recall and transfer, especially to new contexts. Remembering things is important and a significant goal of education, but remembering is the product of higher order thinking, not the other way around. Involving students in comparing and contrasting, drama, and using metaphors and examples are strategies to move quickly into higher order thinking.

Student Voice & Choice: Few people like being told what to do, but in reality, we all have things we have to do that may not be interesting to us or that we would not choose to do on our own. Nowhere is this truer than for children in school. So, how can we entice people to do these things? We often resort to rewards or punishments when we don’t know what else to do, but other blog posts discuss just how counterproductive and highly ineffective they are. Instead, provide students voice and choice. Let them decide how they will do those things. This doesn’t mean allowing students to do whatever they want, but it means giving them choices Let students design learning activities, select resources, plan approaches to units, provide feedback about how the course is going, and make decisions about their learning.

Continuous Improvement: Continuous Improvement takes skilled guidance, direction, and coaching from thoughtful teachers, who will place emphasis on assessing frequently, providing timely formative feedback, coaching, motivating and nudging, and monitoring of progress. Learners need to know what they are aiming at (clear picture of the learning target), and to see fairly immediately how they did with meeting the target. They can gather the feedback themselves, or a guide or coach can provide the feedback (or both). But that feedback needs to be as immediate as possible, and needs to be detailed enough to lead to improved performance. Learners need the opportunity to make corrections on their next turn (and, therefore, need opportunities for next turns!), and the next turn needs to be soon after the current turn. This isn’t about letting students just try and try and try until they get it. To focus on “re-do’s” is to focus on the wrong part. It is about strategically leveraging the clear target and the detailed feedback to improve performance.

Real World Connections: This focus area is often a missing motivator for students. Schools have long had the bad habit of teaching content out of context. Unfortunately, this approach produces isolated islands of learning, and often makes it easy to recall information learned only when they are in that particular classroom, at that time of day; they are not as able to apply the information in day-to-day life. When learning is done in context, people can much more easily recall and apply knowledge in new situations (transfer). Making real world connections isn’t telling students how the content they are studying is used in the “outside world.” It’s about students using the knowledge in the authentic ways people use the knowledge outside of school. Effective strategies include finding community connections, giving students real work to do, and finding authentic audiences for work (think project-based, problem-based, and challenge-based learning).

These six focus areas aren’t new material; they are a synthesis of what we’ve known about good learning for a long time. The model is comprehensive, developed from education research, learning theories, teaching craft, and the voices of underachieving students.

But it is important to keep in mind that students need some critical mass of these strategies to be motivated. Teachers sometimes get discouraged when they introduce a single strategy and it doesn’t seem to impact their students’ motivation. The trick then isn’t to give up, but rather to introduce more of the strategies.

Then my colleague, Alice Lee, who is doing graduate work in learning through technology, shared with me a professional learning opportunity one of her classmates had created.

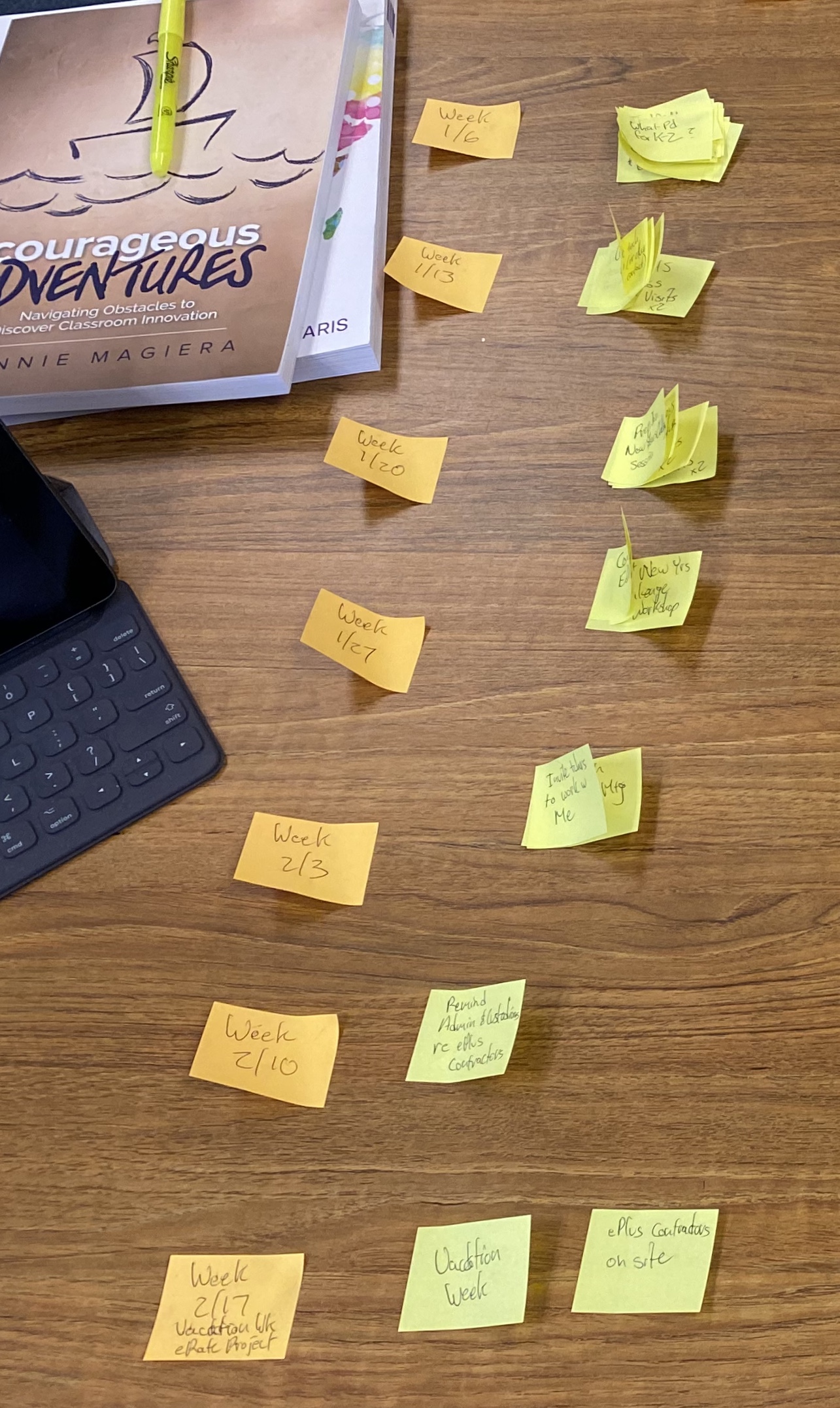

Then my colleague, Alice Lee, who is doing graduate work in learning through technology, shared with me a professional learning opportunity one of her classmates had created.  I started to lay out all our immediate tasks on small Post-It notes and then set them out by week, over the next 7 weeks.

I started to lay out all our immediate tasks on small Post-It notes and then set them out by week, over the next 7 weeks.

And yet, now that I’m a tech director in a small rural (yet, technology-rich!) district, responsible for expanding their learning focus on education technology, I’m discovering that

And yet, now that I’m a tech director in a small rural (yet, technology-rich!) district, responsible for expanding their learning focus on education technology, I’m discovering that

Bethel is wonderful small town nestled in a beautiful section of Western Maine. The White Mountains raise all around us here. There is a beautiful downtown with a well stocked, but relatively small, grocery, and an old fashioned hardware store across the street (Ironically named Brooks Brothers!). And there are plenty of really good restaurants – mostly because the town sits between two popular ski resorts. But it will take 30-40 minutes in any of four directions to find a big box store.

Bethel is wonderful small town nestled in a beautiful section of Western Maine. The White Mountains raise all around us here. There is a beautiful downtown with a well stocked, but relatively small, grocery, and an old fashioned hardware store across the street (Ironically named Brooks Brothers!). And there are plenty of really good restaurants – mostly because the town sits between two popular ski resorts. But it will take 30-40 minutes in any of four directions to find a big box store. the road. I had two:

the road. I had two:  One of the truly challenging parts of leading large-scale school change is how upset some people can be about the change (

One of the truly challenging parts of leading large-scale school change is how upset some people can be about the change ( I’m writing in opposition to LD 137.

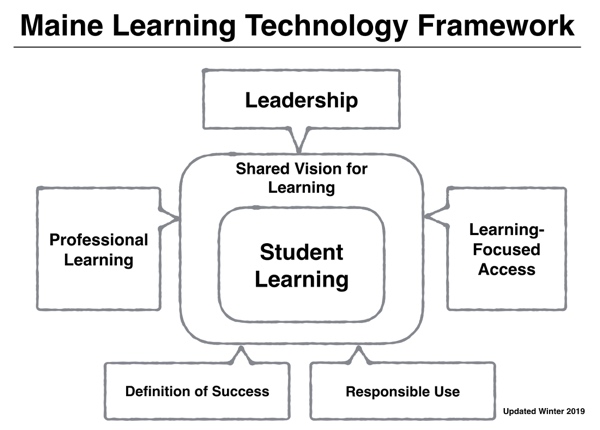

I’m writing in opposition to LD 137. The Maine Learning Technology Framework describes the key elements and components needed to achieve the greatest learning benefit from a district’s technology investment. The Framework is intended to support teachers, tech leads, librarians and other school leaders in their efforts to leverage technology to improve student learning experiences related to learning targets and outcomes.

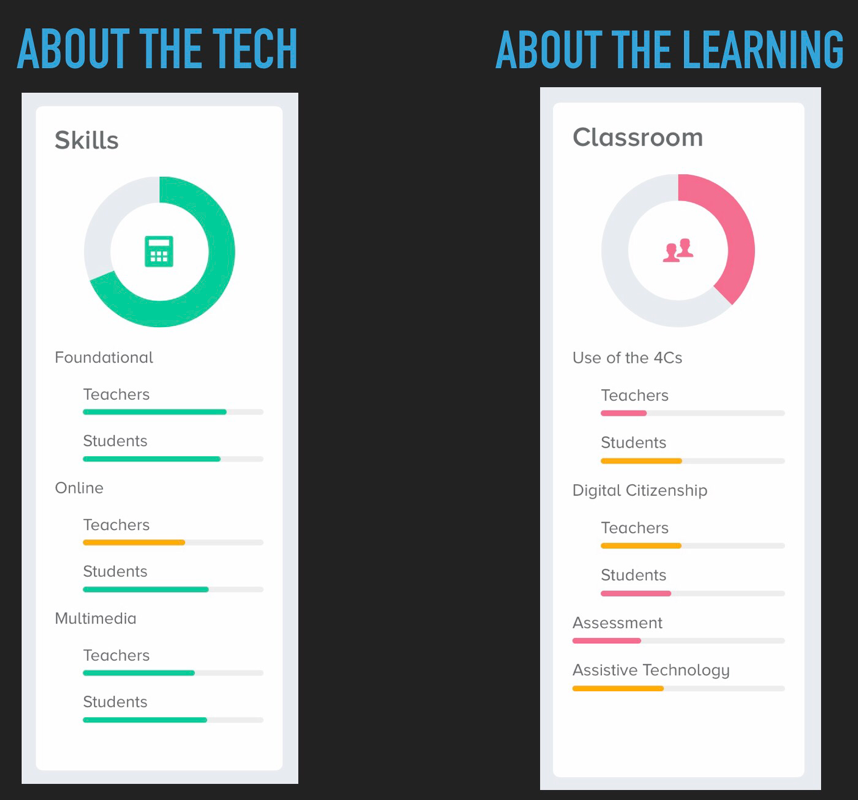

The Maine Learning Technology Framework describes the key elements and components needed to achieve the greatest learning benefit from a district’s technology investment. The Framework is intended to support teachers, tech leads, librarians and other school leaders in their efforts to leverage technology to improve student learning experiences related to learning targets and outcomes.

A really wonderful professor of elementary educational technology, Ralph Granger, used to say, “When you go to the hardware store to buy a new drill bit, you don’t really want a drill bit. You want a hole.” When it comes to educational technology, we need to talk less about our “drill bits” and more about the “holes” we want.

A really wonderful professor of elementary educational technology, Ralph Granger, used to say, “When you go to the hardware store to buy a new drill bit, you don’t really want a drill bit. You want a hole.” When it comes to educational technology, we need to talk less about our “drill bits” and more about the “holes” we want. One approach to creating the conditions for student self motivation are the 6 Meaningful Engaged Learning Focus Strategies which grew out of me dissertation so long ago. Schools working to improve student motivation, engagement, and achievement concentrate on balancing six focus areas:

One approach to creating the conditions for student self motivation are the 6 Meaningful Engaged Learning Focus Strategies which grew out of me dissertation so long ago. Schools working to improve student motivation, engagement, and achievement concentrate on balancing six focus areas: